Martyrdom and Meaningful New Year’s Resolutions

We have the power to treat our own lives as sacred.

As the New Year approaches, I find myself thinking about martyrdom and the archetypal energy of the Martyr. At its core, martyrdom involves self-sacrifice. All new beginnings necessitate endings, and, for us to begin again, we must sacrifice our previous selves—a process that is also the essence of the ritual of making and keeping New Year’s resolutions.

The description of “martyr” is sometimes used as a form of the highest praise, as in the worship of Jesus Christ. Other times, it is used as a pejorative, as in the description of mothers who wield sacrifices for their children in manipulative ways. Historically and within more collectively-oriented societies, the idea of self-sacrifice has often been revered. In our culture with its focus on the individual, self-sacrifice is often derided. The powerful archetypal energy of the Martyr can cut both ways and, as with all archetypal energy, has its positive form and its shadow. Similarly, the perception of a martyr is determined by the perspective of the person doing the observing and can result in the same instance of self-sacrifice being viewed in diametrically opposed ways.

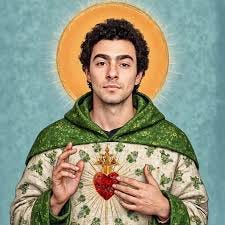

We have recently seen an unusual number of instances of ostensible public martyrdom, but the interpretations of those situations depend on who is doing the interpreting. For example, some see the Israelis killed by Hamas during the attack on October 7th as having been martyrs, while others see the members of Hamas who have died as having martyred themselves. Some perceive Aaron Bushnell, who self-immolated in protest of Israel’s killing of Palestinians, to have been a martyr. Others view his death as meaningless or an act of mental instability. One of the most prominent recent examples of the two edges of the evocation of the archetypal energy of the Martyr and differing perceptions of the same act has been around the alleged shooting of the CEO of UnitedHealthcare by Luigi Mangione. Some view Mangione as having virtuously sacrificed his future life to make a statement on behalf of a suffering collective and have even colloquially canonized him, while others view him as a cold-blooded killer or a “terrorist” and have legally charged him accordingly.

Essential to martyrdom is not bodily death or harm to oneself or others. Rather, what is essential to invoking the archetypal energy of the Martyr is that one makes sacrifices of oneself and that those sacrifices serve to bear witness to one’s beliefs or values. The word “martyr” is derived from the Greek word martus (μάρτυς), which means witness. Martyrdom is, at its core, a form of testimony. For testimony to have the most meaning, it needs to be rooted within a collective.

As the New Year approaches, many people are considering making New Year’s resolutions. The tradition of making such resolutions dates back about four thousand years. New Year’s resolutions have evolved over time from promises of fealty to the reigning king in the Babylonian era to sacrifices to the gods in the Roman era to commitments to more moral behavior under Christian strictures to the current secular assertions of intentions toward self-improvement. New Year’s resolutions in the modern day are essentially a statement of our personal values in advance of self-imposed hardship that will serve as testimony to those values. Our promises are preparation for sacrifice based on what we consider important. However, in our culture and unlike in the past, this ritual is now usually observed only by ourselves as a primarily internal process, and a connection to a greater collective such as a ruler, a god, or a community is largely absent.

If we want to give the making of New Year’s resolutions greater meaning in our time, we can approach doing so differently in a couple of ways. We can sacralize this ritual by focusing our commitments to change on the impact of those changes on the lives of others, thereby rooting them in an external collective. We can also recognize the internal collective within our own psyches, which includes the part of ourselves observing the ritual and to whom we are, in fact, committing. Rather than making superficial promises we know we will not keep and will laugh off later with some degree of shame at our failure, we can make conscious the simultaneous existence of the part of our psyche making the commitment and the aspect of our psyche who will judge us later. Instead of engaging in a mere performative task that is doomed to fail in part because of a lack of wider or deeper connection, we can involve both our acting self and our observing self within the process.

In other words, we can consciously acknowledge that we are actually doing something sacred when we make New Year’s resolutions: We are calling upon the powerful archetypal energies of the Martyr. We are sacrificing and saying goodbye to our old selves and making commitments to our future selves based on what we value in our lives. We are professing those values explicitly and planning to testify to them through actions involving some degree of further self-sacrifice. We are ending, and we are beginning again. Our new selves will be different in some way, in the service of either a communal collective or our collective self.

One role of the archetypal energy of the Martyr is to give meaning to suffering. In writing this, I have come to realize that I am thinking about how to renew the power of New Year’s resolutions at the end of this particular year in part because I know—as we all know—that the coming years will likely involve great suffering over which we will be largely powerless. During a period when many of our lives are going to be increasingly devalued by the system in which we live, taking our own lives seriously is all the more important. Whether or not we are are people of faith, we can take our own lives seriously enough to imbue them with greater meaning. We all have that much power at least: We can treat our own lives as sacred.

May we all have a happy and meaningful New Year—and may we remember that every day is the beginning of a new year.